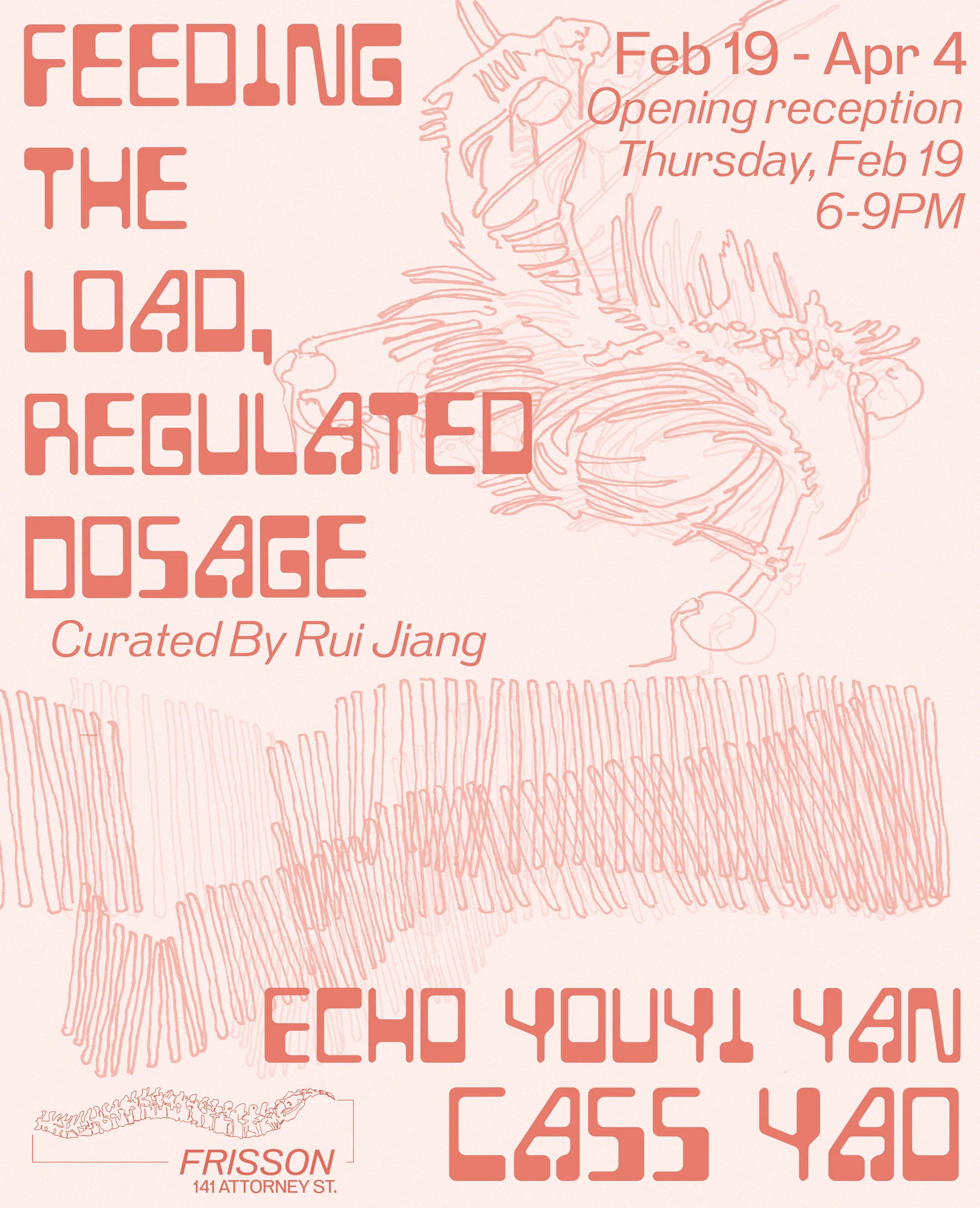

* FEEDING THE LOAD, REGULATED DOSAGE *

* FEEDING THE LOAD, REGULATED DOSAGE *

Feeding the Load, Regulated Dosage

February 19th - April 4th, 2026

Opening Reception: February 19th, 6pm - 9pm

Echo Yan and Cas Yao

Curated by Rui Jiang

Between adaptation and defiance, between the body that submits and the body that rots in refusal, between the weight that sculpts and the weight that crushes—Cass Yao and Echo Yan pull the skin off domestication, peeling it back to expose the raw, trembling architecture beneath. The body does not belong to itself. It is gnawed on by history, sucked dry by function, fattened for slaughter, hollowed for utility. It is an ecosystem of contradictions: a vessel that mutates, decays, heals, betrays, and conspires against itself. A body is never just a body—it is a site of trespass, of forces embedding themselves into muscle, seeping into the marrow, whispering instructions from within. What remains is not flesh but a structure built to withstand, to accommodate, to endure. But what if endurance is just another word for submission? What if survival is just the body’s slow, methodical domestication, its weight rearranged, its angles blunted, its edges tucked neatly out of sight?

Mutation is not a choice; it is an inevitability, a force without a face, an appetite without a master. It slithers through the bones of species and individuals alike, feeding on repetition, on need, on the quiet violence of adaptation. A body bends—because it must, because the pressure is ceaseless, because stillness is death. But in the bending, something else occurs: a mutation that escapes its captors, a crack that refuses to close, an organism that shifts, twists, and, in its disobedience, breeds something new. The body is not a sculpture but a wound that will not scar over, an opening where power and resistance knot together in an unholy, unending embrace. Here, in the grotesque mess of transformation, nothing is fixed, and nothing is free.

Both artists trace the violence embedded in adaptation—how survival demands transformation, how transformation extracts a cost. The body, once a site of presence, now flickers between categories, its agency diffused, its identity multiplied, its flesh laced with the residue of machines and markets, of histories and ghosts. They ask: When does the weight of survival become indistinguishable from control? Can a body absorb its own domestication without becoming it? And in the residues—where shape falters, where function collapses—does something unscripted, something ungovernable, still remain? To be human is to be a process, a temporary configuration of forces, an ongoing negotiation with weight, function, and need. Yao and Yan carve into this negotiation, revealing the cracks where material resists, where mutation outruns its own logic, where the body ceases to be an end and becomes, instead, an unstable passage toward the unknown.

Echo Yan’s work gnaws at the slow violence of domestication, where bodies do not break but soften—rounded, dulled, folded into furniture, tamed into usability. A body adapts, conforms, and forfeits its edges, but the act of yielding is itself a burden, a pressure that sinks into bone and muscle. In her work, the line between life and object collapses—flesh becomes a passive structure, while objects grow eerie appendages of sentience. This is the posthuman recursion: the chair and the body, the egg and the organism, the organic and the synthetic—each absorbing, metabolizing, and reforming into the other. A chair sprouts thorns, rendering it uninhabitable. An egg, fragile and trembling, is both a vessel of life and a pre-packaged commodity, its smooth surface concealing the brutal mechanics of reproduction and control. Limbs retract, not in fear, but in reconfiguration; spines reorient toward the ground, not in submission, but as an evolution into new architecture. A body does not have to be upright to be alive. A body does not have to be human to move.

Cass Yao plunges into the ruptures of bodily modification, where volition flickers between empowerment and coercion. Their sculptures and performances envision the body as a site of perpetual transition, stretched beyond recognition, re-formed under the hands of medicine, violence, or desire. The posthuman body, stripped of its myth of autonomy, becomes an assemblage of prosthetics—biological, mechanical, conceptual—contorted into configurations that exceed humanist logic. To modify is to betray the past self, to distort the lineage, to blur the already fragile boundaries between organism and machine, self and system. The body sheds its inherited shape and takes on new functions, new textures, new dependencies. Muscle laced with circuitry. Skin as synthetic armor. Organs rerouted into metabolic landscapes of intervention. The body is no longer singular, no longer coherent—it is porous, layered, self-devouring. And yet, from this unmaking, the body does not dissolve—it retaliates. It recalibrates, mutates beyond the parameters imposed upon it, festering into a new kind of subjectivity: one that is neither healed nor broken but in a constant state of deviation.

Rui Jiang is a Baltimore-based independent curator and writer. She holds a Master's degree in Curatorial Practice from Maryland Institute College of Art. Her research moves between semiotics, intimate gestures, and shifting dialogues, examining how art forms deconstruct and reconstruct within a polycentric field. She investigates the tensions embedded in exhibition-making—complicity, reflexivity, and the shifting power dynamics that shape artistic discourse. Through interdisciplinary approaches, she experiments with curatorial strategies that challenge linear narratives, embrace contradictions, and reimagine the relationships between artists, audiences, and institutions.